Here’s one for the Downton Abbey fans. Below Stairs (M) by Margaret Powell, originally published in 1968, has been repackaged and marketed as the inspiration for television series like Downton Abbey and Upstairs Downstairs.

Here’s one for the Downton Abbey fans. Below Stairs (M) by Margaret Powell, originally published in 1968, has been repackaged and marketed as the inspiration for television series like Downton Abbey and Upstairs Downstairs.

In reality, Powell did not work in such a stately home with a large staff, but rather her employers tended to be faded gentry who were more likely to be inclined to pinch pennies than to throw lavish parties.

Powell was born Margaret Langley (a name employers felt to be too grand for a kitchen maid) and grew up in a seaside town in a large family with parents who scrambled to make a living. She romantically recalls her childhood as poor, often hungry but never lacking love and laughter. A bright girl, she was awarded a scholarship at age 13 to continue her education, but her parents could not afford to clothe and feed her, so off she went to work. After a few unsuccessful jobs her mother sent her off to to work in service. Since she had no aptitude for needlework she became a kitchen maid, the lowest position, in hopes of learning to cook so she could eventually work her way to this loftier job.

This was the 1920s and employment options for young women were becoming more varied. It became harder for employers to find and keep servants. Powell worked for one clear-sighted employer who understood that a happy appreciated staff would result in her home running efficiently and her family well cared for. She was the exception and most other employers treated their servants with suspicion and in a most patronizing manner. The work was hard, the hours were long and comfort and leisure were scarce. Powell’s ultimate aim was to leave service via marriage and set about finding a husband in the same workman-like manner she approached all her tasks. She had a list – he must not be a teetotaler, he must not be stingy and there was to be no funny business which might get her in trouble before marriage.

This was the 1920s and employment options for young women were becoming more varied. It became harder for employers to find and keep servants. Powell worked for one clear-sighted employer who understood that a happy appreciated staff would result in her home running efficiently and her family well cared for. She was the exception and most other employers treated their servants with suspicion and in a most patronizing manner. The work was hard, the hours were long and comfort and leisure were scarce. Powell’s ultimate aim was to leave service via marriage and set about finding a husband in the same workman-like manner she approached all her tasks. She had a list – he must not be a teetotaler, he must not be stingy and there was to be no funny business which might get her in trouble before marriage.

Below Stairs is a candid, engaging memoir which, at the time, addressed issues which had not spoken about quite so frankly before. Powell exposed the myth of the beloved family retainers and related the reality of working in service with a degree of bitterness that left many feeling uncomfortable at the time. She was not a socialist and she didn’t expect the wealthy to share – she herself said that she wouldn’t share if she were in their position – she merely wanted to be treated respectfully as an individual rather than as a possession.

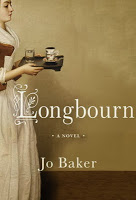

This year we have Jo Baker’s Longbourn (M) which gives us a “below stairs” view of the Bennet family in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

“Here are the Bennets as we have never known them: seen through the eyes of those scrubbing the floors, cooking the meals, emptying the chamber pots. Our heroine is Sarah, an orphaned housemaid beginning to chafe against the boundaries of her class. When the militia marches into town, a new footman arrives under mysterious circumstances, and Sarah finds herself the object of the attentions of an ambitious young former slave working at neighboring Netherfield Hall, the carefully choreographed world downstairs at Longbourn threatens to be completely, perhaps irrevocably, up-ended. From the stern but soft-hearted housekeeper to the starry-eyed kitchen maid, these new characters come vividly to life in this already beloved world. Jo Baker shows us what Jane Austen wouldn’t in a captivating, wonderfully evocative, moving work of fiction.”

“Here are the Bennets as we have never known them: seen through the eyes of those scrubbing the floors, cooking the meals, emptying the chamber pots. Our heroine is Sarah, an orphaned housemaid beginning to chafe against the boundaries of her class. When the militia marches into town, a new footman arrives under mysterious circumstances, and Sarah finds herself the object of the attentions of an ambitious young former slave working at neighboring Netherfield Hall, the carefully choreographed world downstairs at Longbourn threatens to be completely, perhaps irrevocably, up-ended. From the stern but soft-hearted housekeeper to the starry-eyed kitchen maid, these new characters come vividly to life in this already beloved world. Jo Baker shows us what Jane Austen wouldn’t in a captivating, wonderfully evocative, moving work of fiction.”